Responsible AI is dying. Long live responsible AI.

How you, yes you, can help build a better future with AI.

Responsible AI, as a field with a capital R, is in trouble1. While layoffs have affected many, many organizations across the tech industry over the past few years, my perception is that very few with “AI” in the name have been cut as deeply as RAI teams have. I saw two RAI layoffs announced in my LinkedIn feed this morning, after I was already in the midst of writing this piece.

This presents a bit of a conundrum. If every company is becoming AI-first, as nearly every CEO has now stated, one would not be irrational to think that companies should be increasing the staff tasked with ensuring that AI development and usage goes well. Perhaps this is a temporary blip, a symptom of the broader macroeconomic and political environment, and we could see a huge spike in RAI team growth in the next few years. But, I’m not willing to bet on that.

What explains the disconnect between the demand for AI professionals and the lack of demand for RAI professionals? In my view, it boils down to three areas, which I’ve listed in no specific order (violating a personal rule). Note that I’m focused primarily on things that RAI, as a field, could have done differently and not what their parent organizations could have done differently because a) that is what I know best and b) I’d prefer to offer a higher-agency view of potential ways forward. This is in no way an assertion that parent organizations have been perfect partners or sponsors2. As you’ll see, I don’t think any of these areas are monocausal, nor do I think solving any of them is likely to be sufficient to getting the field of RAI back on track, hence the random ordering.

- Insufficient technical proficiency

- Visible failures, invisible successes

- Epistemic overreach and lack of product-market fit

Please note that throughout this piece, I am not taking a specific stance on which values RAI teams should or should not advocate, and do not assume that all RAI teams share the same values. I am not using “values” as a thinly coded replacement for a specific set of beliefs; my argument stands alone as an assessment of how Responsible AI teams have been created and how they have operated.

Despite this, I do think there’s plenty to be optimistic about for developing and using AI responsibly. Small specialized committees and select decision-makers are brittle ways to drive change and outcomes. Instead, we need everyone who cares about beneficial AI to get involved at their own level, in their own role, with their own skills. Living your values is unglamorous and won’t come with a fancy title, but it extends beyond RAI teams and offers everyone a role to play. It’s a bit old-fashioned, but it’s also tried and true.

Insufficient technical proficiency

This is the area in which current RAI leaders have the most potential leverage through both talent attraction and development. When I built my last RAI organization, I had a few non-negotiables: a) hire primarily but not exclusively engineers and scientists, b) use the same hiring and evaluation criteria as the rest of the technical orgs, and c) insist upon continuous technical advancement. I didn’t want the RAI team to be seen as a “destination” for under-performing technical employees nor as an “anti-destination” for high-performing ones. Likewise, if team members ever wanted to move to another team working on AI, they should be equally at home there. I think I was successful at this — some of the highest regarded engineers and scientists at the company sought us out for internal moves and had very low attrition internally and externally.

Note that I didn’t say “hire only computer science majors.” I’m a big proponent of interdisciplinarity. But the simple truth is that technical credibility matters and teams outside of core engineering orgs are often regarded with some skepticism with varying levels of justification.

A common refrain I used when talking about my teams is that “we build tools, not decks.” A common expectation of RAI teams is that they will produce guidelines, checklists, best practices, and documentation for other teams to follow and implement. Many RAI teams come out of design and UX traditions, and are used to engaging this way. This isn’t wrong, but it is not sufficient for success.

Machine learning has always been a technical undertaking, but many data scientists and engineers came from other disciplines with solid foundations in math, statistics, and theory. The rapid advance of AI since the release of ChatGPT, especially in LLMs and RL, has simultaneously increased the engineering expertise needed to be proficient. Deep learning, reinforcement learning, and related areas of AI are highly empirical and often more closely resemble engineering than they do normal science. Magic numbers, hacks, and “we use it because it works” are the name of the game.

To be successful, RAI teams must be able to build and ship the tools and solutions that take their work from idea to production. Relying on other engineering teams to implement their ideas is an anti-pattern in most cases and only increases the perception that RAI teams are less technically adept.

Beyond hiring intentionally, some of the practices I found helpful for staying on top of this are:

-

Ensuring learning on “company time”: setting the expectation that some percentage of one’s work time be spent on knowledge and skill acquisition, along with frequent sharing / “learning in public” with teammates and a long-running paper-reading club.

-

Position memos: AI research is too fast and voluminous to immediately start building the newest and best every day. That being said, it’s not uncommon for a paper to make a splash and for people to start asking when a method / tool / algorithm will be available to use in production. I encouraged frequent one-page memos that outlined what was important or exciting about a given bit of news, why it may or may not work for us, and how we would go about prototyping or implementing it. Importantly, nothing was actually built here, rather it forced us to have a position on a given bit of news as well as show we were ready to deal with it if need be.

Epistemic overreach and lack of product-market fit

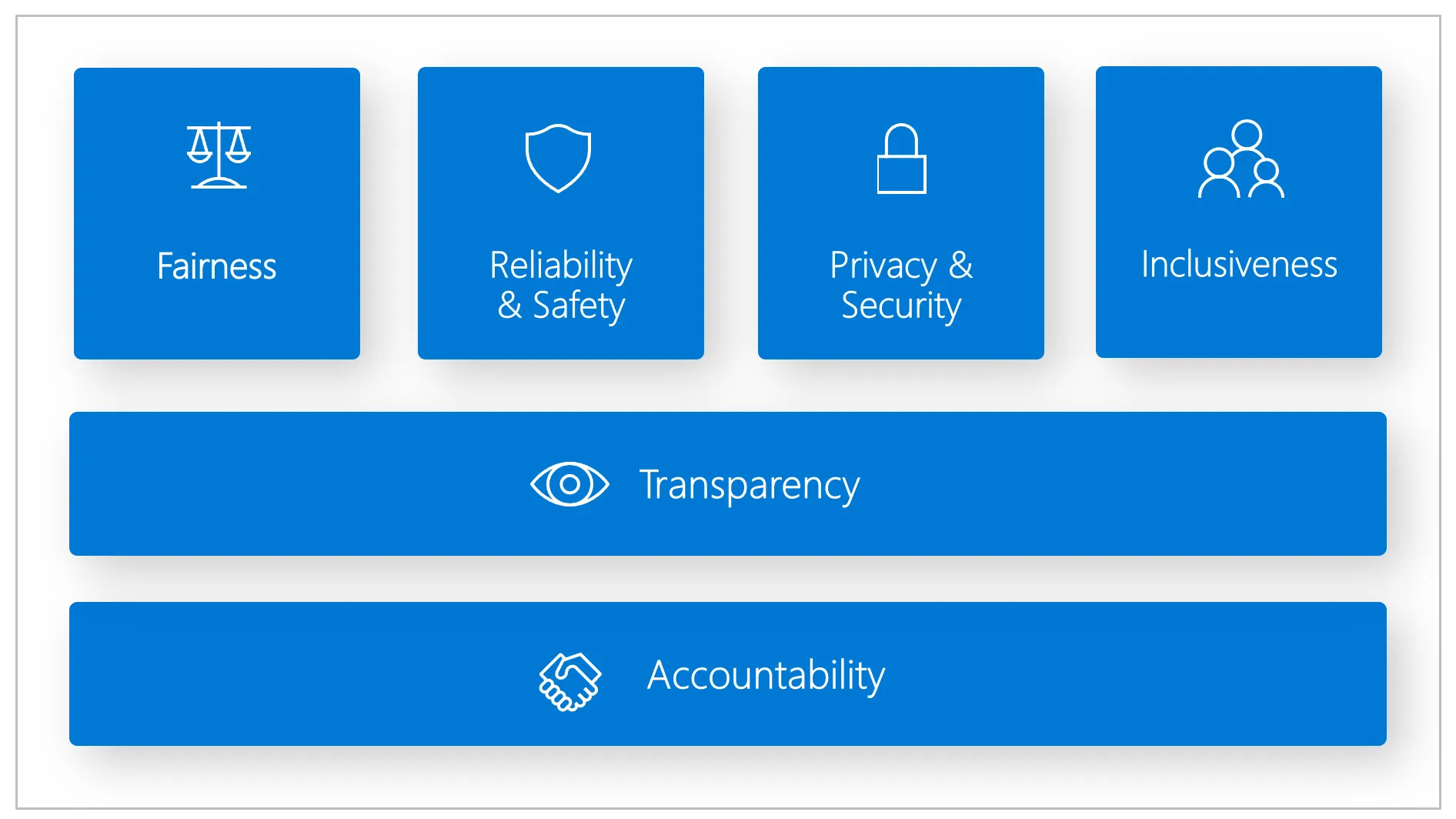

Source: Microsoft

This figure from Microsoft outlines their view of what constitutes responsible AI. Definitions vary depending on the source, but most resemble Microsoft’s in broad strokes. What is remarkable about this is how incredibly broad the scope is. Several of the boxes are typically separate functions or organizations, such as privacy and security. The rest are abstract concepts that require definition and operationalization and often lack clear alignment on what is meant by them. What is accountability? Who is accountable? Can a RAI team determine accountability? Very few companies have the resources to build a RAI team that could feasibly and adeptly cover all of these areas and the ones that could rarely entrust their RAI teams with all of these responsibilities.

If you are a RAI leader and your proposed remit is to prevent bad things related to AI from happening, though, you need to have a point of view on all of these components. Your cross-functional colleagues and leaders may or may not have the same view as you as to how AI intersects with these areas. They may lack experience or expertise with AI. By defining the problem space of RAI so broadly, we’ve ensured that no one can reasonably work across all of them with sufficient expertise. No other part of product or engineering org, to my knowledge, tries to define itself so expansively. Even CTOs and Heads of Engineering / Product have subordinates who specialize in each of these areas. This may well be a fatal flaw for RAI teams so constituted.

Doing well vs. doing good

However, I’m not sure the remedy is a narrower definition. I think, if push came to shove, many RAI teams would argue that their core foci are fairness, accountability, and transparency. In non-zero-interest rate times, to say nothing of the current broader political climate surrounding anything with a whiff of DEI, this is going to be a losing proposition for all but the most values-driven companies. Too many executives, across much of the ideological spectrum, simply do not believe that it is possible to both do well and do good. Winning will always require compromises around the margins of “doing the right thing.” The executives who are truly committed to a values-driven mission tend to self-select into specific companies with similar approaches or are encouraged to moderate.

The formation of the field as “AI Ethics” didn’t help here. Positioning a small number of relatively politically homogenous people, many of whom are proudly anti-capitalist, as the ethical arbiters of AI development made the alliance between them and leadership tenuous at best. Despite research to the contrary, business and ethics being at odds is as close to a core belief as you can get for many senior leaders. I won’t argue whether this is misguided or not because it’s essentially a social fact at this point and its truth or lack thereof is inconsequential for its impact.

Some RAI teams will weather this climate by focusing more on legal and regulatory compliance. I think this is most likely the right move from a team survival standpoint. If a team’s ultimate goal is serving the interests of users and stakeholders, this is where the rubber meets the road. Legal and compliance teams are not immune from layoffs, but most enterprises cannot effectively do business without them. These are some of the few teams with the actual authority bestowed upon them to block releases, demand modifications, and generally provide oversight. Acting in this capacity, however, looks very different from the cutting-edge work that many RAI teams were doing over the past few years. It’s often much more adversarial and less collaborative; most product and engineering teams are simply seeking a sign-off before shipping their work. These teams are not expected to positively contribute to product development or offer inputs beyond their narrow expertise.

Academic influences

RAI teams often pull heavily from academic research and attract academic émigrés. As a former would-be academic myself, I know the reputational baggage that this carries: impracticality, not execution-focused, not focused on business outcomes, incapable of balancing velocity and rigor. I have personally found these stereotypes to be overstated.

The academic field of Responsible AI, and its close cousin AI Ethics, has become increasingly distinct from industrial Responsible AI and has assumed the role of full-time technology critic. Rather than offering solutions, many academics are more openly hostile to industrial AI work. This isn’t a critique of that approach per se; most academics would not claim solutions as within their purview. Critique and criticism are vital, to be sure, but many of the once academicians that seek out industry jobs are often looking to get away from those approaches, not perpetuate them.

Lacking a theory of change

All of that said, there is usually a kernel of truth in the academic cliches. Many RAI teams have created complex and impractical frameworks for their companies to adopt without being able to offer dispositive evidence of their effectiveness. Unfortunately, few RAI teams have a theory of change accompanying these frameworks beyond “we need you to implement our frameworks.” Without strong executive support or the technical ability to embed this work into the tools that engineering teams use, there are usually no repercussions for failure to do so. The benefits proposed by RAI teams often rely on product teams wanting to do so while usually facing incentives that are not aligned with doing so.

When corporate benevolence started to wane, the missing theory of change became obvious rather quickly. Rather than picking the right fights, some RAI organizations picked nearly every fight — sometimes quite publicly3, perhaps attempting to shame their employers into action. It only took minimal shifting of economic and political winds for corporate leaders to question why they were paying significant sums of money for teams that seemed ambivalent at best and hostile at worst to the overall existence of their businesses in the first place.

When an RAI team has positioned itself not only as the team that will stop bad things from happening with AI, but as the very moral and ethical voice of the company, it has unfortunately created an environment in which it is not only difficult to make trade-offs in the name of pragmatism, but actively unethical. Unfortunately not only for the RAI teams but also for users, this is a usually road with no off-ramp other than out of the company.

Visible failures, invisible successes

If you were asked to name notable RAI contributions over the past few years, you’d almost certainly more easily name some of the spectacular misses than any resounding successes. From Gemini putting people of color in Nazi-esque uniforms to telling users how much glue or how many rocks they should eat a day, it’s easy to recall examples of RAI overreach (for the former) or a seeming lack of RAI altogether (in the latter). Not to mention claims of LaMDA sentience by an RAI team member. Lest you think I’m singling Google out here, Kevin Roose’s encounter with Sydney, a Microsoft ChatGPT implementation, was clearly a failure of the literal front-page test as well. There are more, but I’ve made my point.

On the flip side, can you name major successes that RAI teams can claim? Unlikely, unless you are at a tech company with an RAI team doing great work (as I was until recently) or just follow the AI news reallllly closely. This is an unfair question, to be clear. Most RAI orgs task themselves with preventing bad things from happening, and it’s difficult to report on a counterfactual4.

Defense may win championships, but this isn’t football

Many organizations tasked with defense rather than offense face this challenge. Few companies highlight their security teams at product launches or (unironically) thank their legal teams for all of their hard work in keynotes. When “privacy” is mentioned, it’s usually as an abstract concept or highlighting a product feature rather than acknowledging the actual privacy team. And, given this asymmetry, a single “failure” is inevitably going to have more visibility than any number of combined “successes.”

The hard truth is that RAI lacks an “up-and-to-the-right” metric that product, engineering, marketing, and other teams have. RAI teams as currently constituted will probably never contribute to revenue. Once, years ago, an attorney even cautioned me against using “potential fines / revenue losses prevented” as a framing device for the magnitude of a project’s impact as it could be interpreted by litigants as evidence that non-compliance was considered. It’s an uphill battle.

Unfortunately, the whole problem of “visible failures, invisible successes” is exacerbated by two of the other problems I’ve outlined here — epistemic overreach and lack of technical proficiency. By claiming extremely broad stewardship over basically “all the ways that AI can go wrong”, RAI teams have set themselves up to be on the hook for mishaps of all kinds that would normally be accounted for by other teams and they lack the technical proficiency to build the safeguards and tools needed to reduce the risk of mishaps.

My main takeaway from this is that RAI teams should endeavor to make more good things happen instead of solely focusing only on trying to prevent bad things from happening. This requires technical proficiency — launching new features, fine-tuning models, releasing custom embeddings, owning production services, contributing to product roadmaps, building PoCs, etc.

Long live responsible AI

If you have strong feelings that RAI teams are standing between us and rampant AI-induced societal ills, this has probably been a tough read, even if you found yourself nodding along to parts. While I’m clearly not a Pollyanna about the state of RAI as a field, I’m also not a Cassandra. It’s quite clear from popular discourse, even excluding Bluesky, and from opinion polling that a lot of people are concerned and anxious about what the future of AI holds for them. In my last role, I spoke to a lot of customers. Executives who admitted to knowing almost nothing about AI would still ask questions about the potential for bias and discrimination, for the risks to users, and for their own businesses. It’s clear that people care a lot about responsible AI, even if revealed preferences indicate that many companies don’t care about Responsible AI.

Ultimately, centralizing Responsible AI into a single team / org was probably necessarily to get the field off the ground, but that it was never likely to be the final form. Even companies with full-time ethicists (to my knowledge) don’t have Responsible Engineering or Responsible Product teams. Instead, non-RAI teams function as independent organizations, sometimes beholden to a given set of values of codes of conduct, but constituted of individuals with diverse sets of values and commitments.

If you’re currently working in a Responsible AI team and think my diagnosis is even partially correct, I’d offer a few recommendations. First, invest in yourself technically. Right now, technical ICs are royalty. Second, get involved in shipping. To quote Cal Newport, be so good they can’t ignore you. Demonstrating that you can build technical solutions to problems is the surest way to get other leaders to take notice. This has never been more feasible with agentic coding tools and LLMs as personalized learning assistants.

If you’re not in a Responsible AI team, or are simply worried about the future, don’t despair. Teams, orgs, and companies hold themselves to specific standards, while others do not, but it is the result of many decisions and actions that ultimately encode and embed any of those standards into their work. A small set of people making those decisions creates fragility and brittleness which becomes apparent when challenged. This is simply the nature of complex systems.

There’s a certain comfort in that knowledge for me and hopefully for you as well. Hiding beneath is the fact that individuals, no matter their title or role, bring their own values to work with them on any given day and can choose how they live those values. They can decide not to work for companies that don’t share their values or to not use products made by those companies. They can choose to be the voice of responsibility on their own teams, by advocating for their values and encouraging the team to align on what they feel is right. They don’t even have to do this in the name of Responsible AI, merely in doing what’s best.

Exercising your agency in the name of your values has never been an easy strategy, nor has it always been a successful one. Values, like people, are diverse. You may not share the same values as others; but only you get to decide what they are.

Footnotes

-

Yes, the title says that it is dying, but that was merely the result of my N=1 mental A/B test about which headline would land better. ↩

-

I predict many readers of this piece will skim over this sentence, as Twitter has long predicted. ↩

-

This is an honest-to-goodness human-generated, not-slop em-dash. 😎 Deal with it. ↩

-

Kingsman, a cheesy and violent action movie best consumed on an airplane, takes this joke to its extreme by showcasing a wall of newspapers with anodyne headlines that are all front pages of days in which the Kingsmen, a clandestine government agency, prevented something terrible from happening and thus, prevented news. ↩